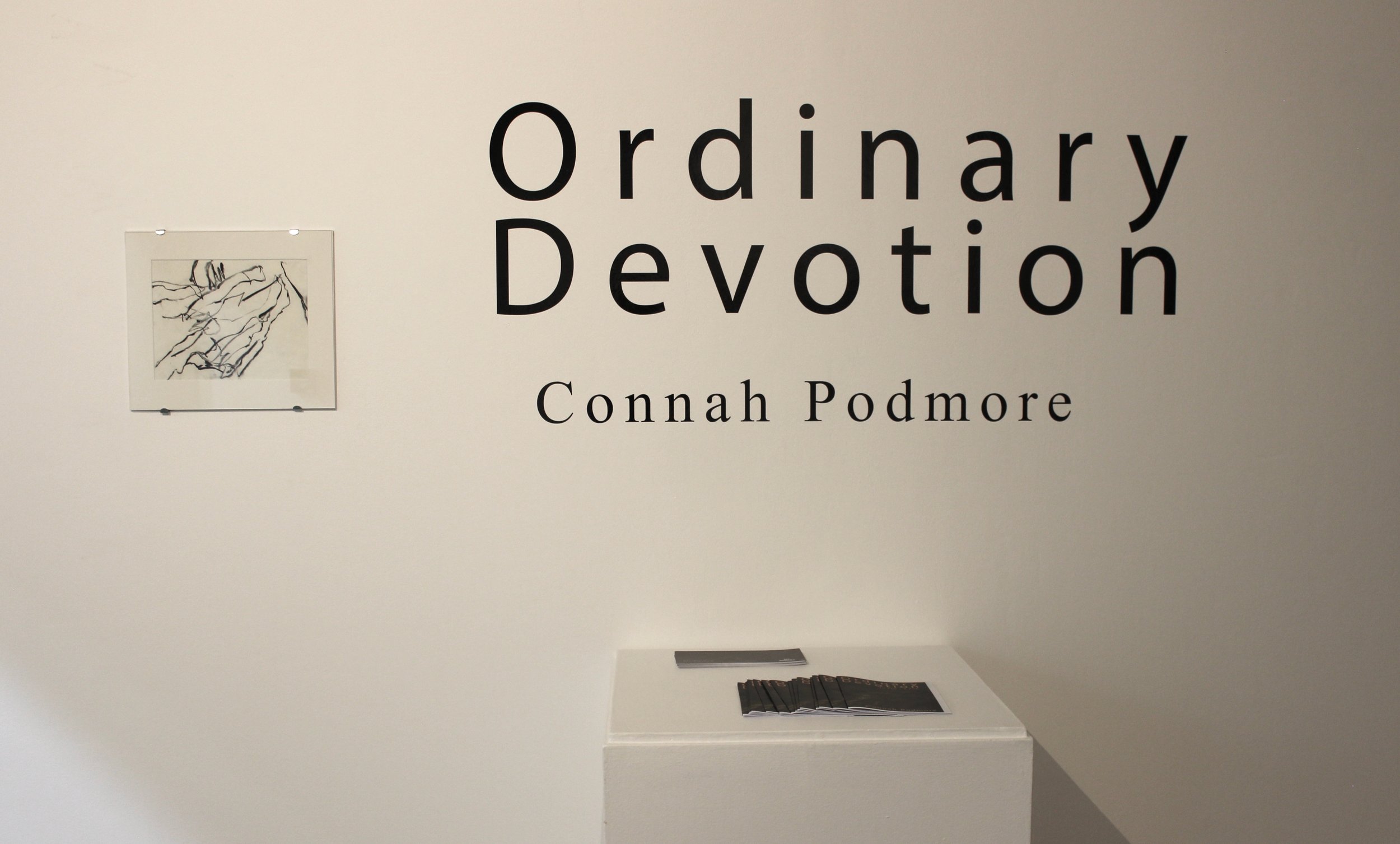

Connah Podmore

13 January - 9 February 2024

Just hold me tight and tell me you'll miss me, charcoal on paper, 1040x800 mm. 2023.

Ordinary Devotion is an installation of drawings and simple architectural interventions reflecting on domestic space and motherhood. This artwork stems from an established line of work exploring interior surfaces, shadow and the many individual histories layered within our homes.

Ordinary Devotion is solo exhibition of original drawings, weaving and photography by Pōneke artist Connah Podmore.

An essay in response to Ordinary Devotion by Connah Podmore by Flora Feltham.

The baby and I are sitting on the living room floor, surrounded by a moat of board books and plastic toys, discarded snacks and every tissue from inside the tissue box, pulled out in a pleasured frenzy by the baby while I was doomscrolling. From the wash house I can hear the washing machine sing its tinkly little song. The baby has also just puked a little milky puke and she places her chubby hand into the pool on the carpet front of her. She rubs it in gently, mesmerised. I must remember to scrub it out. For now, it’s time to sling the baby onto my hip because we are going to hang out the washing!

‘Up?’ I say to the baby before I reach down towards her. This is a manoeuvre we practice many times an hour, like small-time acrobats working their hardest. I hold her firmly under both arms and lift. Her little legs go kick-kick-kick in the air (a flourish), but as I bring her towards my body she is all focus and technique: turning slightly and transferring her weight, she settles against me in one smooth move. Finally she places her right hand on my upper arm, her left hand on my chest and we’re ready to go. She sits there with the composure of a koala.

Caregiving’s Influence on Art

Panel discussion with Connah Podmore, Johanna Mechan and Flora Felton.

Saturday 27 Jan, 2-3pm

Join artists Connah Podmore and Johanna Mechen, and writer Flora Feltham, as they discuss some of the inspiration behind Podmore's exhibition Ordinary Devotion, and the influence that domestic environments has had over their respective practices.

Drawing Essence of Place

Drawing workshop facilitated by Connah Podmore

Saturday 28 Jan, 11am-1pm

$35 booking essential

Over this 2 hour workshop, using family photos as source material, the artist Connah Podmore will help you to draw out a feeling and strip-back content to create a simple but evocative charcoal drawing. Places are limited so bookings are essential. You are welcome to bring a collection of family photos, or photos of a personally significant place along to the workshop to use as source material.

To book please e-mail: artscentre@wcc.govt.nz

I haul the washing out of the top loader one-handed as elegantly as I can. I brace the baby between my arm and hip, then lean sideways down into the machine, dragging bunches of sopping clothes up and over the side before dropping them into the basket. I’m surprised that this is how I move now: a clumsy dance partner to appliances. I used to take all those buttons and handles and lids for granted. Such ease. Until the baby was born I had never made a cup of tea one-handed or thought about how to prop open the fridge with my foot while I poured milk.

The baby warbles. She has made a discovery. A bee, trapped on the windowsill between the glass and the Persil, is buzzing frantically and donking itself, glass Persil glass Persil glass Persil. This is the second bee in the house this morning, and god knows what number bee this week, because this is the season of bees in the house. They get waylaid during their annual pilgrimage to the neighbour’s rhododendron because the neighbour’s rhododendron mostly lounges over our side of the fence, straight out the backdoor. It drops a lush carpet of purple flowers all over the ground, before the petals get blown into the house by the wind and crushed into our floor. Little bruises. Dead bees line the windowsill of the wash house.

I can’t rescue the bee one-handed, so I lower the baby to the lino. We practice the dismount. Luckily, my bee-rescuing tools are just on the bench: a large glass, thick paper. It feels good to use my two hands in easy unison for once and the bee buzzes straight out the door and off into the rhododendron.

‘Right, where were we?’ I say to the baby. She flaps her arms and squeals. Getting out the door is a funny stop-start journey, like the answer to some riddle, where first I carry the washing basket, then the baby, then the washing basket, and then the baby again, traveling in increments of a few metres each time so I don’t lose sight of either baby or basket as we make our way out to the washing line.

The baby sits on the ground while I peg up clothes and explain each garment as way of distracting her from eating the purple flowers at her feet. Here comes another bloom! I unpeel it from her closed fist and add the flower to the list of everything I have stopped her from eating since breakfast. A bottle cap, a leaf, newspaper, two hair ties, a cherry stone, dirt, a Christmas bauble, all those tissues. The washing provides an alternative record of our morning. Sleeves that were covered in Weet-Bix paste and dribble are now wet and clean. Hanging out clothes is one small cleansing act of resistance against the entropy of our days. I try not to think of about the flies around the compost bin. The mouldy shower. The overflowing nappy bucket, starting to smell in the heat.

When the washing is all on the line I say ‘Up?’ to the baby and we practice our routine once more. The lift. Kick-kick-kick. Settle.

Inside, I coax the baby into her highchair. The baby: whacking a spoon on the plastic tray, practising her outside voice inside. Me: turned towards her, keeping one eye on this sliver of my soul, while I Google ‘how to prepare broccoli for babies’. Broccoli: soon to be chopped-up and boiled on the stove.

The broccoli is crunchy and fresh and I can feel the knife exercising its weight to slice through the stems. I eyeball a floret. Big enough so that the baby can pick it up, but small enough so the baby won’t choke? I…think so.

‘Is that right, bubba?’ I say to the babble of syllables coming from the highchair. I chuck the broccoli in a pot of water (no salt) and test it every 30 seconds. Soon my tongue is burned, and the broccoli is crisp enough for the baby to grip, but soft enough for someone with only two teeth to chew. I run the florets under cold water before I pass them to her. I fillet a nectarine for the baby too, removing the skin so her gums can get through the sweet fruit. Before, I could practically ignore nectarines. I would bite into them without thinking, as I stood up in the kitchen. But now. All this attention that my hands used to pay to my husband and to my weaving, to the pages of books and to the sea, to my greasy hair and my stained clothing, now all belongs to the nectarine. I love it. I hate it.

To the baby the world is a research project, to be touched and smelled and licked. She approaches her broccoli and her nectarine with the diligence of a professor. She eats with one hand. Then two. Now, slowly. Now, fast. She picks up bits of fruit from her lap and waves them in the air. She chats with her mouth stuffed like a squirrel. She is surprisingly elegant. Her grace, in her crown of broccoli.

The baby rubs her eyes when she’s finished, squeaks a bold syllable.

‘Are you all done?’ I ask. I seem to speak only in questions to her. When I wipe her hands and her face she protests, squirms away from my grasp. ‘Na na na na na na!’ An answer. Her small tongue has wrapped itself around a new consonant. When I lift her from the highchair, broccoli cascades from her lap and onto the floor like lunch confetti. I must remember to clean it up. This is the satisfying way a day flows with a baby: each task suggests the next. Take her to the change table. Take off her pants. Drop them on the ground. Remember to put them on to soak. Wrestle her legs into fresh pants.

A bee buzzes in the washhouse. Did I put my paper and my glass on the bench again?

We go back to sit among the rubble on the living room floor and that is when the baby poos. I know she’s pooing because she goes unusually still and makes long, direct eye contact with me. Her face turns bright pink. She grunts. I stifle a laugh and gaze back into her eyes. It’s only fair, after all. She has to tag along to the toilet and watch me piss many, many times a day. ’Up?’ I say when she’s done.

We return to the change table where I take off her pants and open her nappy. Ah. Purple flowers: congealed and brown.

The baby is tired now too. She shouts and flails her legs and wails while I try to distract her by singing. But she isn’t happy and she doesn’t know it so she only shrieks and shrieks and bats at the wet wipes. Soon enough I fold her into a cuddle, her clean bare bottom in the crook of my elbow, and as she calms down—making big gulping breathes into my chest—I feel her pee run down my arm. Fuck.

But, in the end I stand there so long, slightly damp and lightly swaying, that the baby sighs and then yawns. This is my cue to draw the curtains. Which I do, still holding her close, with as little movement as possible, so the room darkens around us slowly slowly slowly. I conjure another tiny night, just for her.

When I breastfeed the baby before a nap she is always calm and deliberate. She snuggles in and, on the border of some sleepy horizon, closes her eyes while she glugs milk. When I look at her face I am gobsmacked by its perfection. I can’t believe, under this soft skin, that she has all the teeth she’ll ever need. She is so great in her littleness. A moth. Soon she is milk drunk and I am beauty drunk, both briefly content, certain the universe is good and right. At that time of day, you could tell me anything and I would believe you. So passes an hour.